Artists exhibiting :- Carolyn Barker-Mill, Jay Batlle, Henry Bourne, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Joan Dannatt, Cyprien Gaillard, Jonathan Gent, Duncan Hannah, Paul Heber-Percy, Charlotte Hodes, Joanna Kirk, Alastair Mackie, Kate MccGwire, Simon Moretti, Orlando Mostyn-Owen , Grayson Perry, Humberto Poblete-Bustamante, Jean-Baptiste Marot, Anthony Palliser, Philip Taaffe, Jan Worst.

__________________________

OF CURIOSITY

by Adrian Dannatt

Suddenly, I became indifferent to not being modern.

Roland Barthes

‘I lower my eyes when I walk past an antique shop, like a seminarian passing a night-club’, admitted Henry de Montherlant concerning his obsessive collecting, and likewise whenever my children spy any sort of bric-a-brac emporium they push me across the road or blinker my sight like a carthorse, to ensure they will not be thus delayed. For some of us (the disbelief of discovering that it is not all of us) find such places irresistible, time-consuming and potentially ruinous, to the point where we must be eventually weaned off them. The time-worn analogy with addiction, narcotics or alcohol, seems closer to medical fact that mere turn-of-phrase.

The key to it all seems to me ‘curiosity’ and the attendant curious lack of it in some people, the other people; curiosity as a principle motor of daily conduct, aesthetic discovery and everyday ethics, the wanting to know about other people and their lives, historic or actual, and their objects. Ye Olde Curiositie Shoppe or plain Curiosity Shop strikes me as an excellent name - however ghastly the reality of any store that would use such a term today - because that is the central fact about those who own and frequent such places - an unquenchable curiosity about the world, its inhabitants and their varied creations. These are shops for those of us with a genuine curiosity, who will speak to strangers to discover their life-stories, or at least eavesdrop their restaurant conversation, look at what is hanging on the walls of the same restaurant, and discreetly eye the furniture, furnishings and decoration of any house where they should be welcomed.

All such might seem self-evident, but it is surprising how specific and rare is the actual character-trait of real curiosity. Not the generalised, vague term ‘curiosity’ which everyone in the world automatically assumes they share, but the real thing in its active, if not incursive, application. W. H. Auden said ‘a true friend is someone who reads your mail when you are in the other room’ and in that same ambiguous, sometimes annoying manner the genuinely curious, the curiosity-hunters, are ‘true friends’ to the world and all its effects.

It is this same curiosity which unites both the specialist antique dealer or collector with the contemporary art connoisseur, irrespective of how different the objects involved might appear. Of course all art was contemporary once upon a time, at the time of its making, and the very special and tangible excitement of such art is due to its newness, its freshness and often its unexpected demands. Seeing something new and having to deal with its seeming banality or originality, adjusting it to the canon of art history, or indeed rejecting it, just the act of ‘processing’ its claims and forms, is highly enjoyable - No, it’s rubbish, yes, it’s interesting, well, it’s both, not art, yes art, too ugly, too easy, too odd, and yet and yet…. The pleasure is that the decision is up to you, right there, faced with something made last month and trying to stake its place in the long future to come. Whereas, most works in the museums, the old-master galleries, have already had the decisions made about them, have already been ticked, approved and passed on into the future.

There is an obvious difference, indeed a diametrically opposed principle, between things on display in a contemporary art gallery and an antiquarian gallery. In the former one is looking at things of untested value and novel risk, things that may actively attempt to disown all antecedents, that refuse the ‘anxiety of influence’ in suggesting a new direction for the subsequent making of art. In the latter the objects are tied to the past, to already established values and hierarchies, and it is specifically how they are linked to history, and the closer the better, that gives them importance; their precedents and their pedigree, their provenance, is crucial to their continued value today.

Also, there are the actual aesthetic characteristics of the object, its appearance, shape, colour, size and specific signs. Who made it and when it was made, is equally important to both contemporary and antiquarian collector but above all else remains the question of whether this thing appeals, intrigues, touches one, somehow grants a pleasure, intellectual or instinctive.

In that wonderful phrase of the late French artist Robert Filiou, ‘art is what makes life more interesting than art.’ It is art that can make one look at the world in a new manner, with a more precise or critical edge. And ever since Duchamp’s ‘Readymade’ when we see art which looks like things we do not consider ‘art’, we have to think longer and harder about what makes something ‘art’, about the specific properties of all such objects, their ‘thingness’. We are just obliged to be a bit sharper, smarter, to see so.

Any really good antiquarian gallery, like any really good contemporary gallery, will serve as a sort of laboratory for the active testing of your sense-of-response, for your awareness. Thus if you are a curious person there can be nothing more enjoyable than to put yourself through such a battery of tests - Why look at that, what could that have been used for, how beautiful, how improbable, how was that made, why was that made, how impossibly grand. The principle motivation of every antiquarian dealer should be the same boundless curiosity - What will I find next, how many of these exist, why was this made, that drives the contemporary art world.

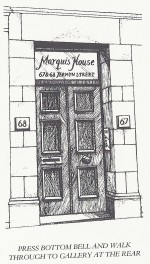

Curiosity is certainly the ruling principle at Harris Lindsay Works of Art, which as its full title suggests welcomes a wider definition of ‘art’ than just painting, drawing or sculpture, precisely as contemporary practice also insists upon a far more ambitious scope to the term. A work of art should in itself help expand the boundaries of its own definition. At Harris Lindsay there is emphasis on ‘workmanship’ and on aesthetic intent, the art being both in the skill of the maker as well as in their imagination. The relevant criteria here are the quality of design; the quality of execution; the historical context.

Hence, the rightful insistence on the correct word; that this is an ‘antiquarian’ dealership, meaning dealers in rare and unusual objects of interest to collectors and academics, rather than simply dealers in decorative antiques. Harris Lindsay welcomes the widest range of human creation from any time and any place, from the Neolithic to the neo-neo. Whether in a seminal exhibition on Danish design covering the modern period from 1920 until 1970, or the present display of heraldic ‘beestes’ once belonging to Henry VIII, the intention of Harris Lindsay is to open one’s eyes, to share their own passionate curiosity, to try to understand just why this particular object is as it is. So, in their 2003 Danish Modern exhibition catalogue, the question is posed right at the start - Why exactly was this furniture made in Denmark and at this time? And thus a recent exhibition such as the Hawkins Zoomorphic Collection, in which a truly extra-ordinary range of objects created from animals was displayed in an ideal setting, pushing the boundaries of ‘good taste’ if not the ‘politically correct’ in a manner all too familiar to the contemporary art world.

But quite apart from a shared curiosity for the object-of- life, Harris Lindsay provides, so obviously, a wonderful environment to put together an exhibition of contemporary art, as much for its happy congruities as differences. A vocal boredom with the accepted ‘white cube’ model of presenting contemporary art is becoming increasingly loud. When Charles Saatchi presented his collection in the old fashioned wood-panelled warmth of the old County Hall he made clear his disaffection for the standard blank white concrete space, and openly spoke of his interest in other ways of showing such work. Indeed there is a whole micro-history, an alternative tradition, of such strategies of exhibition, whether Dr. Barnes’ mansion, Peggy Guggenheim’s ‘Art of This Century’ designed by Frederick Kiesler, or Gertrude Stein’s apartment on the rue de Fleurus.

The oft-acknowledged precedent for a certain type of such an exhibition is the wunderkammer, a curiosity cabinet, or kunstkammer, a debt made overt in the show ‘Feux Pâles’ at the CAPC Bordeaux, organised in 1990 by the extremely radically conceptual artist Philippe Thomas. Indeed, curiously, it is often the most soi-disant ‘conceptual’ contemporary artists who are most interested in other means of displaying their art, perhaps because they are so aware of the immediate history of art-curating and theories on the presentation of important objects throughout history.

Another crucial example of this would be the show ‘Retrace Your Steps: Remember Tomorrow’ organized by Hans-Ulrich Obrist at the Sir John Soane Museum in December 1999, in which individual, often very discrete contemporary art works were oft indistinguishable from the original décor. Likewise, the 2005 show ‘Past Presence’ at the Getty Research Institute and Grolier Club, starred the earliest known copper-plate engraving of a curiosity cabinet from 1622. As they put it :- ‘The wide-ranging display looks at how artists … responded to notions of time and the urge to capture a moment, recreate the past, record the present, or imagine the future’. More recently, two exceptional exhibitions have been mounted by Joe La Placa and his All Visual Arts organization, ‘The Age of the Marvellous’ and last year, ‘Vanitas: The Transience of Earthly Pleasures’, held in Great Portland Place. In Sydney there have been a series of contemporary shows mounted at Elizabeth Bay House and supported by the Historic Houses Trust, whilst at Pallant House in Chichester, under the knowing eye of Stefan van Raay, contemporary art is cleverly and pleasingly incorporated into an 18th Century setting.

Such institutional examples of truly imaginative presentation are rarer, perhaps because the bureaucratic mindset moves so much slower, but Peter Noever’s groundbreaking installation of his MAK in Vienna, of 1986, can still seem shocking, with its rare antique furniture presented by modern artists, most notably Donald Judd’s pitch-perfect re-design of the permanent Baroque collection. Of equally exceptional quality is the Musée de la Chasse in Paris which has managed to integrate contemporary art works into an historical collection and building in a flawless manner, a mise-en-scène of utter charm.

Of course, one could also suggest that there are now, and always have been, contemporary artists whose interest in the codes and practices of the past are precisely their radical novelty. And this makes them particularly suitable to exhibiting in a context more sympathetic to the historical than the minimal. Indeed there is a continual claim that the truly ‘radical’ or truly ‘reactionary’ (in the sense of reacting to its own era) contemporary art is always that which proposes a ‘return-to-order’, a ‘traditionalism’, neo-neo-classicism or postmodernism. This is an ‘eternal return’ in itself, distant as such now vanished issues as the battle between ‘ancient’ and ‘moderns’, or between ‘abstraction’ and ‘figuration.’

And certainly I would never want to suggest that the artists in this current exhibition belong to any movement or even loosest of groupings, whether ‘Romantic Conceptualism’, ‘Aristocratic Neo-Realism’ or ‘Theoretical Figuration’. No, the only thing that temporarily unites these very disparate artists is that I think they are very good, and that certain of their works might build an engaging and ideally enlightening exhibition within this specific context. If the ‘historical objects’ in this show already belong to Harris Lindsay, they have still been selected or conjoined by myself for their resonance with the contemporary art, such possible combinations and rewarding clashes, aesthetic or intellectual, being the very essence of the curatorial aim. The contemporary art should as much mettre-en-valeur the historical objects as vice versa, the present influencing the past, encouraging the spectator to question the values and codes of both domains equally and simultaneously. A whole range of issues, a whole other essay, might be provoked by such synchronicities and oppositions, between the hand-made and the mass-produced, the workshop and the atelier, the signed and the anonymous, the practical and the perversely purposeless.